Why even progressive women now yearn for the 1950s

It was an era of rapidly and equitably distributed economic growth. Increasingly, those too young to have experienced it fantasise about returning to it

A few days ago, in the city where I live, thousands of Australians trooped into a convention centre to adoringly drink in the wit and wisdom of Barack Obama. Tickets were in the $200-$800 range, so it’s fair to assume most of the crowd were upper-middle-class progressives who continue to see Obama as a Messianic figure.

I wasn’t there but the 44th president of the United States reportedly acquitted himself well, as he usually does. Just like a touring US rock band doing a cover of an AC/DC song, he made an effort to tweak his schtick to flatter the prejudices of the Australian audience, getting in a jab at Murdoch. Lamenting the hyperpolarisation of recent times, he drily observed, “There’s a guy you may be familiar with, first name Rupert, who was responsible for a lot of this. He perfected what is a broader trend... it’s now a Wild West and a splintering of media.”

But what most interested me about Obama’s speech were his thoughts on what he described as the “winner-take-all” economy. Depending on how narrowly you want to define winner, either 20 per cent, or 1 per cent, or 0.1 per cent of the population have been winning massively since the post-war boom and, shortly thereafter, the dominance of Keynesian economic policy came to an end in the mid to late 1970s.

On the other hand, vast swathes of the population have been losing since then. Throughout the neoliberal era, most first-world individuals have either been experiencing downward social mobility or having to study and work harder and harder to keep their crampon lodged in the upper-middle, or even just middle, class. (As luck would have it, a day after Obama’s speech in Sydney, figures were published showing that 0.1 per cent – that is, one in a thousand – of Sydney homes and apartments were affordable to those on the average household income. In Melbourne, the figure was a whopping 2.2 per cent.)

From what I can make out from media reporting, Obama first argued technological progress “has weakened the ability for the average worker to get a fair share of the overall production, and it has greatly exacerbated inequality to levels we haven’t seen since the 1920s. It’s also exacerbating the gulf between nations. That is a recipe for polarisation and people are getting angry and frustrated and resentful”.

He then observed many people in the Anglosphere felt “screwed over” by globalisation. Veering close to self-criticism, Obama even noted, “There was a little bit too much arrogance about free markets and free trade, and anybody who’s questioning jobs being moved offshore, they’re backwards looking, and ‘everybody’s going to be a coder some day’. It turns out when people’s lives are disrupted, [and] entire communities or entire industries feel disrupted, you better have some good answers for them, and we haven’t always had those.”

You can say that again, Barry.

A short history of the world

Human history can roughly be bifurcated into two eras – the pre-agricultural and the post-agricultural. During the first era, everyone was poor because, leaving aside animal pelts and shiny stones, there was no wealth to accumulate. Agriculture changed everything and a select few individuals did start to accumulate wealth. Nonetheless, most of humanity remained incredibly poor. After the industrial revolution, living standards (eventually) improved for everyone and left-wing political movements began agitating for a more equitable distribution of wealth and power. However, the vast majority of the population remained mired in grinding poverty and even members of the ruling class had to endure primitive conditions. (In ye olden days, even aristocrats and plutocrats didn’t have access to anaesthetic, air travel, dentists, electricity, indoor plumbing or penicillin.) Child mortality rates were shockingly high and even those who did make it into adulthood were often dead before their fortieth birthday.

Things started to turn around for humanity, especially the hoi polloi, in the 20th century. Sure, there was a Great Depression and a couple of World Wars to navigate, but anyone born from about 1925 onwards could look forward to a lifestyle their grandparents would have found barely conceivable. From circa 1945 – 1975, life got much better for everybody in the Anglosphere (and many people in Europe and parts of Asia).

The long post-war boom was so long-lasting and boomy that people came to believe that ever-greater prosperity and income equality was the natural order of things. Parents were convinced their children would inevitably lead more prosperous, fulfilling and leisurely lives than they had, which is not an assumption a hunter-gatherer, medieval peasant, or 18th factory worker would have made. Given the predictions Keynes made in the 1930s that what we’d now call ‘fully automated luxury communism’ would soon arrive, there was significant concern among the intelligentsia about how people would adjust to leading lives of near-effortless abundance.

That hasn’t turned out to be quite the problem that mid-20th-century intellectuals feared it would be.

Did the post-war boom create unmanageable expectations?

Writers are often fascinated by the decades before they were born. Arguably, the most famous recent example is Matthew Weiner, the creator of Mad Men. Like me, and probably you too, dear reader, Weiner is a Gen Xer. Like me, he is fascinated by the post-war boom and, at least by implication, the difference between the bounteous, optimistic post-war boom past and the rather grimmer post-boom present.

As Mad Men is at pains to illustrate, and Leftist academics, writers and politicians constantly proclaim, the post-war period of rapid economic growth and widespread embourgeoisement also had downsides. But, in retrospect, it sure looks pretty good. Even to some groups who were putatively oppressed.

With remarkable bravery and insight, River Page recently wrote about the burgeoning tradwife subculture in a Substack piece titled ‘The Tradwife Craze is about Envy’. Page suggests many women never wanted to work. Or at least they never wanted to run themselves ragged trying to hold down a job while raising a family.

Unfortunately, Page’s article has gone behind a paywall since I printed it out, but the money quote is as follows:

Ultimately, the only real thing all tradwife creators seem to have in common is unemployment – they don’t have jobs, don’t want them, and don’t need them. The rise of this community and its viral success isn’t due to 50s fashion nostalgia, Christianity, sexual fetishism, or white supremacy, even though various creators might dabble in one or the other. It’s about envy. The tradwife subculture reflects the desires of many American women back at them in a highly stylized fashion. For them, being a ‘tradwife’ isn’t in vogue, it is Vogue – a series of glossy pictures, daydream fodder, a glimpse inside an enviable life they can’t afford. Studies have shown that a majority of American women with kids under 18 prefer the role of homemaker, as did 39 per cent of women without children under 18. Yet a majority of households today are dual income. This isn’t by choice but by necessity. Stagnant wages and the increased cost of living have made housewifery a luxury to be flaunted on social media.

Are Gen Xers, Yers and Zers wearing rose-coloured glasses?

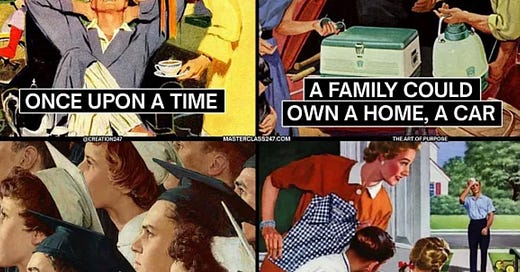

Referencing a meme that shows a jolly American nuclear family enjoying the trappings of 1950s suburbia and that states, “Once upon a time a family could own a home, a car and send their kids to college, all on one income,” Matthew Yglesias recently expressed his frustration with what he labelled “nostalgia economics”.

You can read the entire piece here and judge for yourself, but I’m not sure Yglesias did prove his thesis that “Nostalgia economics is totally wrong”.

To summarise, the 41-year-old, who appears to be of solidly upper-middle class stock – he went to a prestigious New York private school, then studied philosophy at Harvard and, after a storied journalism career, now presumably makes good coin from his popular Substack,

– conceded that it was possible to live a comfortable lifestyle on one income in the 1950s. But Yglesias seems to believe the post-war year sucked because our parents (or grandparents) didn’t have as many devices we do.Sure, the 1950s might look good to today’s Average Joes and Joannes, who can only dream about owning a home and having a job for life, Yglesias admitted. But if you lived in the 1950s, you wouldn’t have had a dishwasher or air conditioning. Labour-saving devices such as washing machines were only just beginning to achieve mass penetration. And don’t even think about having access to life-changing technologies such as “luggage with wheels, microwaves [and] surround sound”.

Food was blander, scarcer and more expensive. Houses and apartments were smaller and some didn’t have hot water. Many people, especially in rural areas, still had to use an outhouse. Yes, many families had one car, but they seldom had two. Far fewer people finished high school, let alone went on to university. If they did go on to tertiary education, they somehow had to obtain a degree in a place of learning with hardly any administrative staff and “no IT team maintaining the campus-wide WiFi network”. There was less government regulation, meaning life was risker.

Perhaps sensing that plenty of people under 50 would be perfectly happy to lead less technologically advanced but more economically and emotionally secure lives, Yglesias concludes his argument by pointing out that American families (and, by extension, families in other first-world nations) could live on one income but choose not to.

As I suspect only someone in his class position would dare to argue, Yglesias insisted, “If you want to have a two-parent, one-income family in a 1950s-sized house with one car and not send your kids to college, you can almost certainly afford that… And you’d even be able to take advantage of modern advances like Netflix, out-of-season fruit, and affordable domestic airfares. That’s just not the life most people choose.”

Hmmm. Except for the wealthy – and I mean seriously wealthy, not merely upper-middle class – I don’t think surviving on one income for a prolonged period has been a feasible choice for any couple with children for at least a quarter of a century. Certainly not if they aspire to live in or near a major city.

Yglesias is on more solid ground when he observes:

The pace of economic growth really was much faster in the 1950s and 1960s. Americans are richer today than they were two generations ago, but we are growing richer at a slower pace… There is something to the fact that this poorer-but-faster-growing period is remembered fondly, but the right takeaway isn’t nostalgia for the past – it’s impatience with the current slow pace of growth.

Of course, that raises the question of why economic growth has been so slow in recent decades and why almost all the benefits of it have accrued to those in the top quintile of the income distribution.

But that’s a topic for another day.

Controversial stuff but a conversation that's worth having (says me ... a card-carrying feminist who had the "good fortune" to walk away from my career and assume a tradwife role, as you call it)